Obituary

Dr. Norma Taylor Mitchell, 86, died Friday, July 7, 2023 at Croasdaile Village in Durham, NC. A committed feminist whose independence, intellect and strength were balanced by warmth and kindness, she made the most of her life in every area. She was an imaginative scholar of women’s and Black history, a progressive church and community leader, a dedicated teacher and mentor, a faithful relative and friend, and a supportive, interested, and generous parent and grandparent. Her family and friends will cherish her memory forever.

Death came peacefully, following a long, slow decline that began after her husband of nearly 58 years, Rev. Dr. Joseph Mitchell, died in 2017. Depression and anxiety invaded the void that he left, and despite everyone’s best efforts and excellent care at Croasdaile, Norma couldn’t shake them. While she retained her presence of mind and sharp memory, her bright, inquisitive spirit had dimmed long before the end finally came. Her family is grateful for the many friends and family members who kept in touch during these final years.

Norma was born on November 14, 1936, in Norfolk, Virginia to Orville Carson Taylor, Sr., a clerk with the city of Norfolk, and Emma Nora Heal Taylor, a homemaker and former teacher who had come to Virginia from Kentucky around 1920. Norma arrived in the midst of the Depression to a family of modest means that already included eight- and thirteen-year-old sons. While her grandmother reportedly thought the addition of another child under these circumstances unwise, Norma Anne was from the beginning a beloved “baby girl” adored by her parents and brothers. Her mother’s death from bone cancer fourteen years later left a lifelong scar and disrupted home life during her high school years. But her doting father and older brothers remained a loving presence the rest of their lives.

Norma graduated with honors from Maury High School in Norfolk in 1954, where she excelled at Latin and was editor of the newspaper. She attended the College of Wiliam & Mary (initially in Norfolk and then in Williamsburg), where she majored in history, was elected to Phi Beta Kappa, and graduated in 1958. Receiving a Southern Fellowships Fund College Teaching Career Fellowship, she matriculated in the fall of 1958 in the History Ph.D. program at Duke University.

Early in her first semester at Duke, Norma met Religion doctoral student Rev. Frank Joseph Mitchell, an Alabama native who had returned to Durham after spending five years serving Methodist churches in Virginia. A speedy courtship ensued, featuring many trips to Durham’s Blue Light restaurant, where Joe bought Norma a hamburger and milkshake and drank coffee himself to save money. (Elements of this dynamic would persist throughout their relationship!)

They were engaged in the spring of 1959 at the Carolina Inn in Chapel Hill and married on September 5, 1959 at Norma’s home church, Park Place Methodist, in Norfolk, VA. They spent their early married years in Durham, living during 1959-60 in the Duke Methodist Student Center while Joe worked as an assistant to the Rev. Art Brandenburg and Norma completed her doctoral coursework, one of only a handful of women in her Duke History Ph.D. cohort.

In 1961, while both continued work on their degrees, the couple moved to Northfield, Minnesota, where Joe taught religion at Carleton College. In 1962, after Joe completed his Ph.D., they moved to the coalfields community of Barbourville, Kentucky, where Norma taught as an adjunct professor in the history and political science departments and Joe served as Campus Minister and Assistant Professor of Religion at Union College (Methodist). In 1964-65, Norma returned to Durham on a Cokesbury Fellowship to continue her dissertation research.

In 1965, they moved again to Fayette, Missouri, where Joe took a position as Professor and Chair of the Religion Department at Central Methodist College. With his encouragement, Norma finished her dissertation on the political career of 19th century Virginia Governor David Campbell. In 1967, Norma graduated from Duke with her Ph.D. in History and had their daughter Anne Virginia. From 1968-70, she worked half-time as Dean of Women at the college.

In 1970, lured by the offer of tenure-line faculty positions for both of them at Troy State University in Troy Alabama, they moved home to Joe’s native state. Censured by the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) for abrogations of academic freedom, Troy was eager to prove it could recruit AAUP members to its faculty. Having served as an AAUP chapter president, and coming highly recommended by a Duke friend then on the Troy State faculty, Joe was an attractive candidate. His and Norma’s membership in Phi Beta Kappa added to their appeal.

The move to Troy – where they spent the next 31 years – heralded a busy, professionally active, and productive period in Norma’s life. Much of her work in the years to follow clustered around her longstanding commitment to the United Methodist Church and a prescient engagement with the emerging fields of women’s and African American history that had begun while she was in graduate school.

While working on her dissertation research in the Duke Libraries, she had been intrigued by abundant archival material documenting the lives of women and enslaved people in the family of the governor whose career was the project’s focus. Compiling the material in a chapter she called “home life” at the governor’s Abingdon, Virginia residence, she presented it to her Duke faculty director. “Take that out,” he advised. “That’s not real history, and no one but a few antiquarians will be interested.”

She removed it, but her professor could not have been more wrong. In the decades to come, this sort of material was what most interested historians, students, and the public, as wave after wave of the “new social history” (history from the bottom up, with far less emphasis on “great white men” and politics) rose and crested. Norma followed her interests in women’s and African American history the rest of her career.

In Troy, Norma and Joe were stalwart members of First United Methodist Church, where every Sunday found the family on the third pew in the center section immediately in front of the pulpit. Throughout the 1970s, Norma became deeply involved in local, conference, regional, and national United Methodist activities.

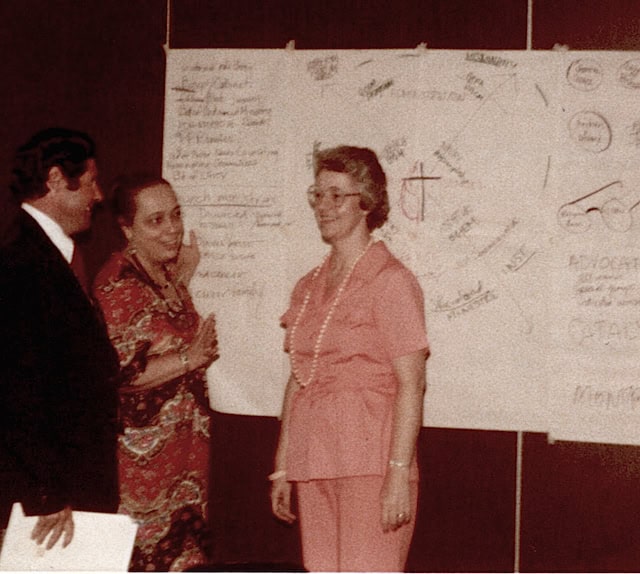

These volunteer efforts included service as president of the interracial Church Women United chapter in Troy; leadership in United Methodist Women and service as founding chair of the Commission on the Status and Role of Women in the Alabama-West Florida Conference; election as a delegate to the 1980 Southeastern Jurisdictional Conference; and eight years as a member of the General Commission on Archives and History for the United Methodist Church. Indeed, church work constituted almost a part-time job for her during those years.

Perhaps her most significant and enduring accomplishment during this period blended her emerging focus as a historian with her commitment to women’s empowerment in the United Methodist church: From 1977-80 she chaired the church’s pioneering Women’s History Project, a wide-ranging public history initiative. In 1980, this project convened a national scholarly conference on women’s history in the Methodist tradition – the first such conference held by a large U.S. mainline religious organization – in Cincinnati, OH. In 1981 and 1982, Abingdon Press published two volumes of papers from the conference under the title Women in New Worlds: Historical Perspectives on the Wesleyan Tradition.

In a bitter irony, the editors of those books refused to include for publication the paper that Norma and Joe had written for the conference, a critical analysis of the status and role of Methodist bishops’ wives (and they were all wives, then) that unsettled some of the powerful in the church. (The paper’s title was “Supporting, Sharing, and Shaking the Patriarchy.”)

Others, however, respected her courageous leadership. The bishop in the Rocky Mountain Annual Conference invited her to serve as the conference keynote preacher during the celebration of the American Methodist Bicentennial in 1984. That invitation provided an opportunity for a memorable trip through Colorado with her then teenage daughter Anne Virginia.

Although she continued her substantive involvements in United Methodist organizations into the 2000s (boards of Scarritt-Bennett Center, Alabama United Methodist Children’s Home, and Birmingham Area Pastoral Care and Counseling), her relationship with the church shifted somewhat after 1980. Still, people in Alabama remembered Norma’s leadership, and in 2013, the Commission on the Status and Role of Women for the Alabama-West Florida Conference honored her with their Alice Lee Award, which recognizes key advocates for women’s equality and inclusion in the church.

Meanwhile at Troy State, while Joe struggled in a series of conflicts with university administration, nearly lost his job, and found himself sidelined teaching general studies courses as the religion major was eliminated, Norma thrived. She was the first female History faculty member at TSU to achieve the rank of Associate Professor (1970), to be tenured (1977), and to be promoted to full Professor (1984).

Life as a Troy State faculty member included a punishing teaching and advising schedule. With three classes per quarter – most meeting every day – Norma sometimes strained under the avalanche of bluebooks. And for five years in the late 1970s, she traveled to junior and senior high schools across southeast Alabama supervising social studies student teachers.

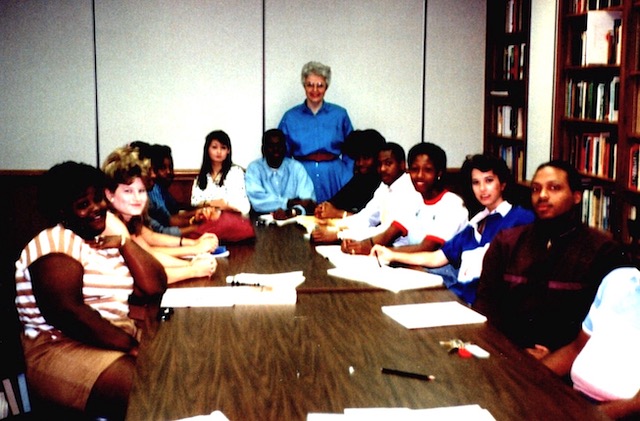

Still, she enjoyed the “stage” of the classroom setting and devoted herself to creative undergraduate teaching across a broad array of topics (from general studies World Religions, Western Civilization, and American History to specialized seminars on early America). A review of the books in her vast library near the end of her life revealed the depth of her reading and engagement with new scholarship in American history, with many books marked in her signature red Flair pen or annotated with observations about how they might be useful in classes. Bringing the new scholarly perspectives to Troy students, she introduced new permanent courses in American women’s history (1981) and African American history (1988).

While she was the adviser or treasurer for the active campus Phi Alpha Theta history honor society chapter through the 1980s and 1990s, she and Joe frequently entertained students and colleagues in their home near the Troy campus. Additionally, Norma mentored many work-study assistants. Many of these students remained lifelong friends years after they graduated.

Always projecting a veneer of Southern elegance, grace and gentility that softened her assertive nature and radical politics, Norma got along better at Troy than Joe did. Although they worked together with colleagues in the 1980s to organize a faculty senate, for instance, it was Norma who became its first full-term president in 1985-86.

After her retirement in 1999, the university honored Norma and her longtime colleague Milton McPherson with establishment of the annual (and still ongoing) McPherson-Mitchell Lecture in Southern History. In 2023, appropriately, the lecture focused on the history of the Clotilda, the last known ship to bring enslaved people from Africa to the United States (to Mobile, Alabama) in 1860.

Although her teaching and service demands at Troy made it difficult, Norma continued to pursue her research on the women and enslaved community within the Virginia Campbell family, as well as a newer biographical project on the life and work of pioneering Alabama physician and Methodist leader Dr. Louise Branscomb. From the late 1980s to the early 2000s, she lectured frequently to scholarly and public audiences and published several articles on both topics.

It is perhaps fitting that her final professional act, in 2017 just after the death of her husband, was to speak with a Washington Post reporter about her research on the women and enslaved community associated with the Campbell family. The letters Norma had uncovered that documented the lives of the enslaved Valentine and Jackson families – brought with the Campbells to Richmond when David Campbell became governor in 1837 – were the focus of a new memorial garden installed in 2016 at the historic governor’s mansion in Richmond. [See Gregory S. Schneider, “The Forced Absence of Slavery: Rare Letters to a Virginia Governor Give Voice to the Faceless and Forgotten,” Washington Post, September 13, 2017, https://wapo.st/3rFOuQZ. Norma’s original article is: Norma Taylor Mitchell, “Making the Most of Life’s Opportunities: A Slave Woman and Her Family in Abingdon, Virginia,” in Beyond Image and Convention: Explorations in Southern Women’s History, ed. Janet L. Coryell et al. (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1998), 74–98.]

Professionally active as she was, Norma was also a thoughtful and engaged partner to Joe in raising their daughter, Anne Virginia, who grew up from the age of three in Troy.

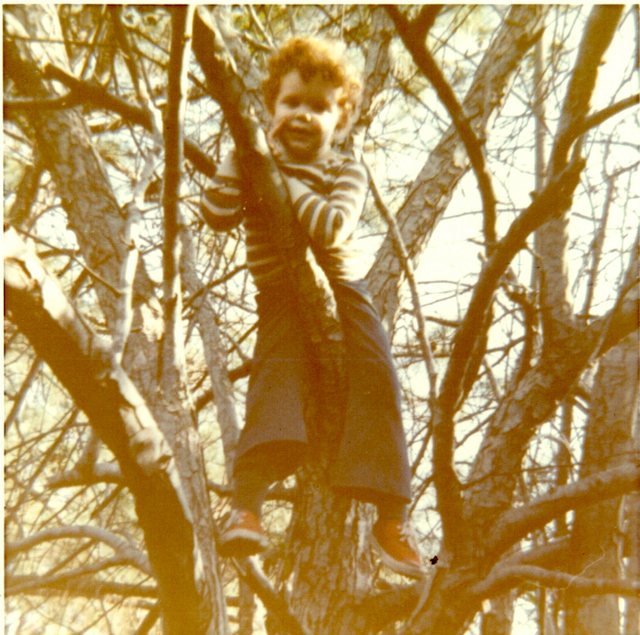

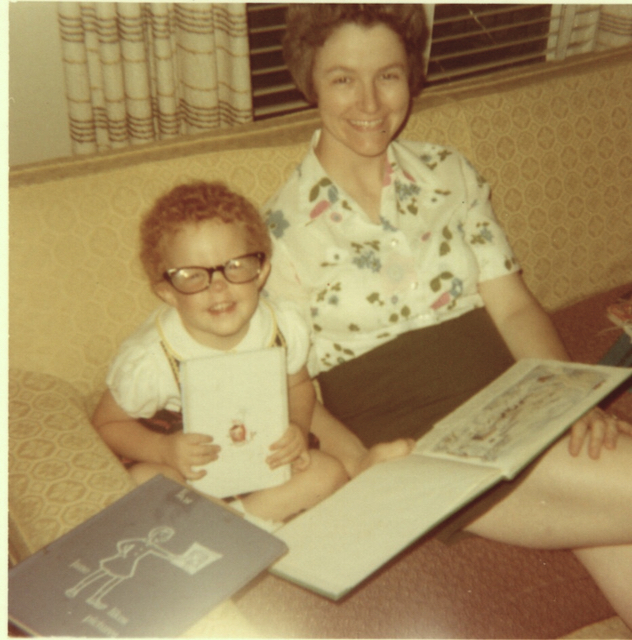

Deeply informed by the feminist politics and parenting approaches of the 1970s, Norma encouraged her daughter’s androgynous tendencies and exploration of her full personhood. She read Ms. Magazine’s “Stories for Free Children” to Anne and brought home the pioneering Free To Be You and Me album. Rejecting her own father’s overprotective impulses, she let her daughter climb trees.

She bought the football helmet and shoulder pads Anne found in a thrift store and let her wear leather moccasins to church (with a dress, of course). She “home-churched” Anne with United Methodist materials when the local church adopted Sunday School literature from the conservative Focus on the Family organization. Despite Anne’s objections, she told her she had to go ahead and make the sewing box craft the Vacation Bible School assigned to girls, but allowed her to smash it in the backyard at home afterwards.

And when the male owner of a small North Carolina bookstore questioned whether she really knew what was in Judy Blume’s Forever and whether she meant to buy it for her preteen daughter standing nearby, Norma replied, “Yes I do, how much please?”

Norma and Joe paid sustained attention to Anne’s education, from elementary through graduate school. They served as PTA co-presidents and followed their daughter to south Alabama high school football stadiums to hear her play trombone in the Charles Henderson High School Blue Machine marching band. When Anne was a Birmingham-Southern College student headed to Zimbabwe with a college service-learning trip in 1988, the college chaplain invited Norma to deliver remarks to the group before departure. And Norma patiently answered the phone through Anne’s angst-filled first year in graduate school.

All along, Norma and Anne shared their love of cats, dogs, shopping at Montgomery and Birmingham malls, and random drives around town and through the Alabama countryside.

In 1989, Joe retired from teaching at Troy and re-entered the United Methodist pastoral ministry, accepting an appointment at the Covenant United Methodist Church in Chesapeake, Virginia. Thus he and Norma began a year of “commuter marriage,” as he moved into the huge Covenant parsonage on the Elizabeth River, and she remained in her faculty position at Troy. During that year, Norma managed their Troy home by herself, made several trips to Virginia, and enjoyed reconnecting with her extended family in the Tidewater area.

In 1990, Joe returned to Alabama, taking a cross-conference appointment in the North Alabama Conference as pastor of the Ensley First United Methodist Church in Birmingham. Norma became a true “pastor’s wife,” engaging regularly with the aging congregation while driving back and forth to Troy to keep up her busy teaching schedule.

After three years of commuting, Joe and Norma decided that Joe would retire completely and return full-time to Troy. Together, they designed and supervised building of a new, custom home in Troy’s Heritage Ridge subdivision. In the fall of ‘93, they moved from the home they had bought in 1970 near the Troy State football stadium to the larger new house on Monticello Drive.

From 1993 until Norma’s retirement from Troy State in 1999, Joe worked daily in his study and played the role of “house husband,” handling cleaning and cooking duties and caring for Norma’s pets he’d always claimed not to like.

In 2000, with two grandchildren, Evan David Whisnant and Derek Taylor Whisnant, having been born to Anne Virginia and her husband David Whisnant in Chapel Hill, Norma told a hesitant Joe: “You are not going to die and leave me a widow in Troy, Alabama.” Early the next year, on Evan’s fourth birthday, Joe and Norma moved back to the progressive community of Durham, to a large home able to accommodate, among other things, their 400 boxes of books and historical and family records.

Joe and Norma settled quickly into the Durham community, joining Epworth United Methodist Church, where Norma was once again a leader on committees focused on programming for older adults, a churchwide study of poverty, and community outreach. She also actively participated in the Orange-Durham-Chatham Branch of the American Association of University Women (AAUW), a national advocacy organization supporting women’s equality in which she’d also been involved before leaving Alabama. She and Joe enjoyed reconnecting with many longtime friends in Durham and traveling to the western National Parks and Canada with the Rev. Max and Ann Wicker, who lived in nearby Southern Pines, NC.

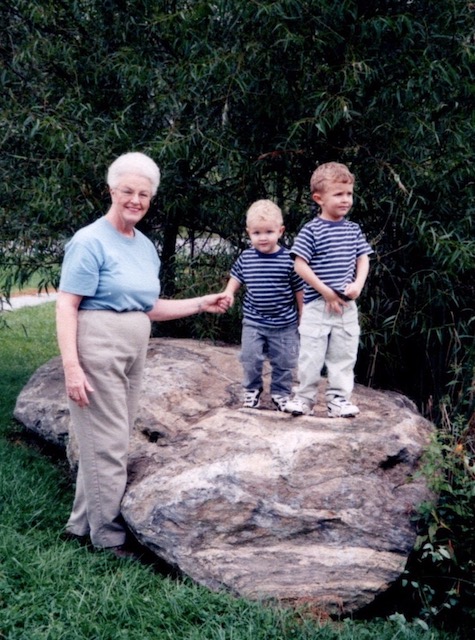

Coming to Durham provided Norma the welcome opportunity to become more involved in the lives of her beloved grandsons. She babysat frequently, took them to local animal shelters and pet shops, and created a welcoming second home for them in Durham. She and Joe took several trips with Anne, David, and the boys — to Lake Junaluska, the Blue Ridge Parkway, Florida, and the North Carolina coast. They attended the boys’ every performance and family event, and made possible many enrichments, including camps, concerts, music lessons, season tickets to the Playmakers theater on the UNC-Chapel Hill campus, and trips to Europe for both boys.

While Evan won a full scholarship to Birmingham-Southern, Norma was pleased to be able to underwrite college costs for Derek at UNC Asheville, and proud to see both boys become third-generation college graduates in 2019 and 2021.

Norma was preceded in death by her husband Rev. Dr. Frank Joseph Mitchell; parents, Emma Nora Heal Taylor and Orville Carson Taylor, Sr.; stepmother Mary Bellamy Taylor; her brothers, Orville Carson Taylor, Jr. and wife Marie Morrissette Taylor, and Randall Heal Taylor; and her brothers- and sisters-in-law Jesse L. Mitchell, Faye B. Mitchell, Seth H. Mitchell, Jr., Kathleen Mitchell, and Wanda Ellis Mitchell; and niece Emma Taylor Wade.

She is survived by her daughter and son-in-law, Drs. Anne Virginia Mitchell Whisnant and David E. Whisnant (Chapel Hill, NC); grandsons Evan David Whisnant and partner Rachel Hoben (Graham, NC) and Derek Taylor Whisnant (Asheville, NC); sister-in-law Joyce Taylor (Bluffton, SC); first cousin Jo Rhea Colonna Ford and husband David Ford (Oxford, Alabama); nieces Elizabeth Taylor McDaniel and husband Tim McDaniel, and Anne Leigh Taylor Stamper and husband Dallas Stamper, all of Virginia Beach, VA; and nephews Robert Harrison Taylor (Virginia Beach) and Randall Heal Taylor, Jr. and wife Julianna Mello Goulart (Savannah, GA).

On her husband’s side, she is survived by nieces Jessica (Jesi) Mitchell Trentham and husband Paul Trentham, and Martha (Marty) Mitchell Roe and husband Howard Roe, all of Asheville, NC; her nephew Joseph Hamilton Mitchell and wife Cindy Mitchell of Mill Spring, NC; niece Sharon Mitchell Sellars and husband Walt Sellars of Fayetteville, GA; niece Sandra Mitchell Hollander and husband Ira Hollander of Fort Worth TX; nephew Seth H. Mitchell III of Fair Oaks Ranch, TX; nephew John David Mitchell and wife Kay Davis Mitchell of Fort Worth, TX; and niece Kathy Halasy and husband Chris Halasy.

Many beloved great nieces, great nephews, and cousins on both sides also survive.

A memorial service will be held on Saturday, October 7, 2023 at 11:00 a.m. at Epworth United Methodist Church in Durham. Lunch will follow in the church fellowship hall. All family and friends are invited to attend.

In lieu of flowers, the family suggests that memorial gifts be sent to the following organizations that reflect Norma’s values:

American Association of University Women (AAUW), Orange-Durham-Chatham Branch, AAUW-ODC, PO Box 9303, Chapel Hill, NC 27515.

https://chapelhill-nc.aauw.net/donate/

- Organization supporting women’s empowerment since 1881 (Norma was a member of this branch, founded in 1923).

Epworth United Methodist Church, 3002 Hope Valley Road, Durham, NC 27707. http://www.epworth-umc.org

- Where Joe and Norma were active members from 2001 to their deaths.

People In Need “PIN” Ministry, 1164 Miller Lane, Suite A, Virginia Beach, VA 23451. https://www.pinministry.org/home

- Nonprofit serving the homeless in Virginia Beach, VA since 2002; started and led by Joe and Norma’s niece, Anne Leigh Taylor Stamper and her husband Dallas Stamper.

Bread for the World, 425 3rd Street SW, Suite 1200 Washington, DC 20024. http://www.bread.org

- Advocacy organization lobbying the U.S. Congress on behalf of hungry people in the U.S. and worldwide since 1974; one of Joe and Norma’s most important philanthropies since the 1970s.

This obituary may be also be found online at: https://www.prisource.com/welcome/anne-mitchell-whisnant-ph-d/obits/